.

mp3: The Magic Flut - Queen of the Night aria

.

mp3: The Magic Flut - Queen of the Night aria

Few artists ever gave such unalloyed pleasure as Florence Foster Jenkins, yet this extraordinary soprano had the wisdom not to overdo a good thing.

She emphatically declined to appear in New York oftener than once a year and rarely anywhere else except such favored centers as Washington and Newport. For years her annual recital at the Ritz-Carlton was a private ceremonial for the select few—her stubbornly loyal circle of clubwomen and the adventurous cognoscenti. If the latter at times displayed an unmannerly lack of restraint they were nonetheless faithful.

Music critics covered the event in precisely the same reverse English with which they frequently, though perhaps less intentionally, leave a baffled public speculating as to what actually did happen the night before. Then the word began to get around. Tickets became harder to come by than for a World Series. Finally, on the evening of October 25, 1944, Madame Jenkins took the big step. Forsaking the brocade atmosphere of a fashionable hotel ballroom, she braved Carnegie Hall.

There are those who claim that her death one month and a day later was the result of a broken heart—as unlikely as the story that her career was all a huge joke at the public's expense—a pretty expensive joke, incidentally, since Carnegie Hall was sold out weeks in advance and grossed something like $6,000. Moreover, the late Robert Bagar wrote in the New York World-Telegram: "She was exceedingly happy in her work. It is a pity so few artists are. And the happiness was communicated as if by magic to her hearers..."

No, Madame Jenkins died full of years—76 to be exact—and, it is safe to say, with a happy heart.

Neither her parents nor her husband gave any encouragement whatever to her musical ambitions, but with her divorce and the money inherited from her father, a Wilkes-Barre banker and lawyer who had served in the Pennsylvania legislature, she was free to turn her sights on new York. She broke into print in 1912 as chairman of the Euterpe Club's tableaux vivants. She was also glad to foot the bill for the annual spree of her Verdi Club. The lavishness of this entertainment may be guessed from the name under which it went—"The Ball of the Silver Skylarks."

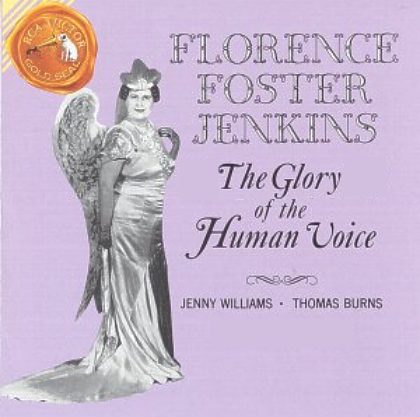

All this gave free rein to her flair for costume design, a faculty that was to prove almost as startling as her vocal nights. No Jenkins recital was accompanied by less than three changes. In "Angel of Inspiration" a very substantial and matronly apparition, all wings and tinsel and tulle, made its way through potted palms to the curve of the grand piano. Small wonder the late Helen Hokinson was an ardent Jenkins fan.

Her method of ticket distribution was also unique and a model of straightforward dealing. In the hands of the scalpers those coveted pasteboards would have brought ten times the price. It is doubtful, however, if this was the reason she insisted on personal application to the genteel midtown hotel where she had rooms. Toying with the tickets as Rosina might with her fan she would inquire:

"Mr. Gilkey, are you a—a newspaperman?"

"No. Madame Jenkins," the applicant replied quite soberly, "a music-lover."

"Very well," the diva beamed. "Two-fifty each, please. Now would you like some sherry?"

Would he? Who wouldn't sit down for a friendly glass with this phenomenon in the musical life of our time?

It is too bad she did not record her favorite encore, Clavelitos, a number she invariably had to repeat. A contemporary account describes Madame Jenkins as appearing in a Spanish shawl, with a jeweled comb and, like Carmen, a red bloom in her hair. She punctuated the rhythmic cadences of the song by tossing tiny red flowers from her pretty basket to her delighted hearers. On one occasion the basket in a moment of confusion followed the little blossoms into the audience. It too, was received with spirit.

Before she would do the repeat, her already overworked accompanist, Cosme McMoon, had to pass among the jubilant groundlings and retrieve the prop buds and basket. The enthusiasm of the audience at this point reached a peak that beggars description.

After a taxicab crash in 1943 she found she could sing "a higher F than ever before." Instead of a lawsuit against the taxicab company, she sent the driver a box of expensive cigars.

Although high coloratura was Madame Jenkins' particular province, she also ventured into the quieter realm of lieder. She opened her 1934 program with Die Mainacht of Brahms. Under the title was this quote:

O singer, if thou canst not dream,

Leave this song unsung.

Nobody will ever say Florence Foster Jenkins couldn't dream.

For some time there has been wide demand for a reissue of this Florence Foster Jenkins album, but it was felt that an attraction should be found to couple with the soprano's recordings.

If it is impossible to predict where the lightning of genius is going to strike, how much less predictable is the urge to artistic endeavor. One day with no advance warning whatever Jenny Williams and Thomas Burns walked into RCA Victor's Custom Record Department. The records they wanted to make were to be for their own use but eventually they agreed to the public issuance of the material on this disc. The English translations are their own and speak for themselves—also for the cause of opera in English.

As Madame Jenkins found her way to the recording studios from the concert hall, perhaps Miss Williams and Mr. Burns, with the start they may surely expect from this disc, will one day attempt to fill, in a measure, the gap left by Madame Jenkins' departure from the musical scene.

Francis Robinson

Assistant Manager of the Metropolitan Opera (1952-76)

and author of "Caruso: His Life in Pictures"